July 8, 2011

Food Security: Cassava’s Evolving Role in Mozambique and Tanzania

Promar consultants Shinichi Kawae and Lucia Vancura together with research partners from Norinchukin Research Institute, recently completed an 8-month project on the cassava industries in Mozambique and Tanzania, as part of a larger project on important African crops sponsored by the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF).

Promar consultants Shinichi Kawae and Lucia Vancura together with research partners from Norinchukin Research Institute, recently completed an 8-month project on the cassava industries in Mozambique and Tanzania, as part of a larger project on important African crops sponsored by the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF).

The project aimed to understand how further development of the cassava industries can help increase food security in the target countries, as well as understand what potential exists to produce value-added cassava products, such as high quality cassava flour (HQCF), cassava chips or cassava for animal feed products.

One of the motivations for this study was that fact that although Africa produces 50% of the world’s cassava and cassava is the main staple in many areas of Africa, the information available in Japanese on the role of cassava in African economies is limited. Promar’s study provides recommendations in Japanese and English on cassava’s potential for helping increase food security and generate income through value-added cassava processing.

Traditionally cassava in Mozambique and Tanzania has been seen as a “poor man’s” food, a staple planted by rural villagers and then harvested little by little as needed. Cassava has already long been playing an important role in food security as it can grow in poor soil, can be left “stored” in the ground for up to 3 or 4 years and less vulnerable to weather and pests as maize or other crops.

But as people’s income’s rise, can cassava compete with maize, or imported wheat? Can adequate cassava supply, processing facilities and transport infrastructure be created to fulfill the new demand for high quality cassava flour in urban areas? These are some of the many questions facing the cassava industries in Tanzania and Mozambique.

Promar’s study discusses issues facing the entire cassava value-chain. It looks at issues related to cassava production, including new variety development, seedling multiplication and cassava plant diseases; infrastructure issues including roads, transport and electricity; and challenges facing the value-added cassava industries, most importantly the unstable and insufficient supply for cassava processing.

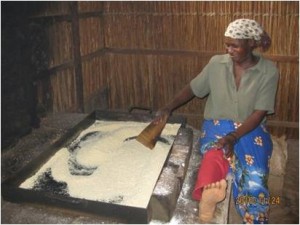

Picture: A Mozambican worker at a cooperative frying fermented cassava flakes (rale) for commercial sale at supermarkets